Let me tell you a little about my dad.

The other week I went for a meal with my sister, brother-in-law, niece, dad and a couple of cousins about four times removed from California.

An ordinary meal with extended family. Perhaps. But it was a little more poignant than that.

It was the search for a dad, for dad, that had brought us together.

My dad was born in 1917 on February 14th. The 1st World War was raging; it was a year before women over the age of 30 were given the vote; just the day before, Mata Hari had been arrested on suspicion of spying; when Tsar Nicholas II abdicated the Russian throne dad was just over one month old.

It never ceases to fascinate me that dad was born when all these sepia, consigned-to-history-books events took place.

But there he is, at 93, the umbilical cord between me – us – and events almost a century ago.

Dad weighed just 2lb when he was born at Victoria Hospital in Burnley. A doctor called MacGregor suggested dad be incubated in a warm drawer to try and keep him alive. He was fed using the tube from inside a fountain pen. Obviously it worked … and dad has forever borne the middle name MacGregor in lasting thanks to that canny medical man.

When dad was about five his dad – Wilfred – left home, never to return. Dad often recalls going into a shop on Manchester Road in Burnley as a little boy, urged on by his own mother, to pull on his dad’s coat-tails and ask for a little money.

But other than that, for practically 90 years, dad – my dad – has never known what happened to his dad.

So step in my sister. The Miss Marple of the genealogy world. Perhaps she’d prefer Jessica Fletcher. I’ll let you know if I survive after this paragraph is published.

To cut to the chase, my sister recorded the memories of my great aunt, who lived to the age of 99 and from that moment she caught the family history bug. She set herself a challenge to track down dad’s dad.

I won’t bore you with the fine detail, but eventually my sister pieced together a family jigsaw which had seen our grandfather bought up with a surname which wasn’t his own; it was his mother’s from a previous marriage.

A woman’s decision to revert to a former marital surname when she was left alone when her husband – our grandfather’s father – left home, confused my sister’s family search. A surname which my dad, his sons, grandson and great-grandson still bear.

A political pamphlet hidden in some of dad’s belongings led to the breakthrough of tracking down dad’s ancestry. Written by JR Widdup, it was a socialist mantra written in Burnley in the late 19th century. My sister explained her discoveries, and requested information, at the time in 2004. She had discovered that JR Widdup – a strident socialist in the late 19th century – was the father of our grandfather Wilfred Widdup. But there was still no sign of him.

It is very odd but once I knew my true family surname – Widdup – I felt as if I’d come home somehow. You may think that’s an odd thing to say, but Marriott had been my maiden name but I had never felt comfortable with it.

It transpired dad’s family had a strong connection to Barnoldswick and the beautiful St Mary le Ghyll Church is the resting place of many of our ancestors. Weddings, christenings and funerals; the church cradles the shadows of long-lost emotions of my forebears in its historic walls. I was moved by those shadows when I visited and had a little weep.

Up until very recently dad knew nothing of this family background. Now he is just as likely to say ‘I should have been a Widdup you know’ as he is to comment on Burnley’s chances of getting back in the Premiership.

Once my sister ‘cracked’ the mystery of my grandfather’s background she was able to trace back the history of the Widdups some way and is even now known as an expert on them.

But still no sign of Wilfred.

My sister also traced back my grandfather’s maternal side – the lady who changed her name to a former marital name. My dad’s grandma. Even she lost touch with her son Wilfred when he moved away, which for years led the family to believe that some tragedy had befallen him, as mother and son were very close.

Her own father Thomas had worked on the railways and was killed at a now-defunct Burnley train station, leaving his widow to bring up her young family. Thomas’ own siblings had already moved away from Burnley with their minister father to a new church in Yorkshire.

It was one of their descendents we met in a pub in Burnley the other week. Herb, dad’s 3rd cousin removed. My sister had found him via the network of genealogists that refer and cross-refer to each other when fellow researchers ask questions and seek information. You help me, and I’ll try and help you, seems to be their informal philosophy.

Since then their internet friendship has developed into a real one, with the family connection coming back together all those years after Thomas lost touch with his own family when they moved away to another town.

So there we were in a pub. Nothing but steak and kidney pie and a few generations several times removed between us.

Dad was so chuffed. Not least because there was one portion of chicken dinner still left in the kitchens. He looked at me and my sister and said ‘ah, there’s my daughters’. He looked at Herb and his wife and said ‘ah, who’d have thought’.

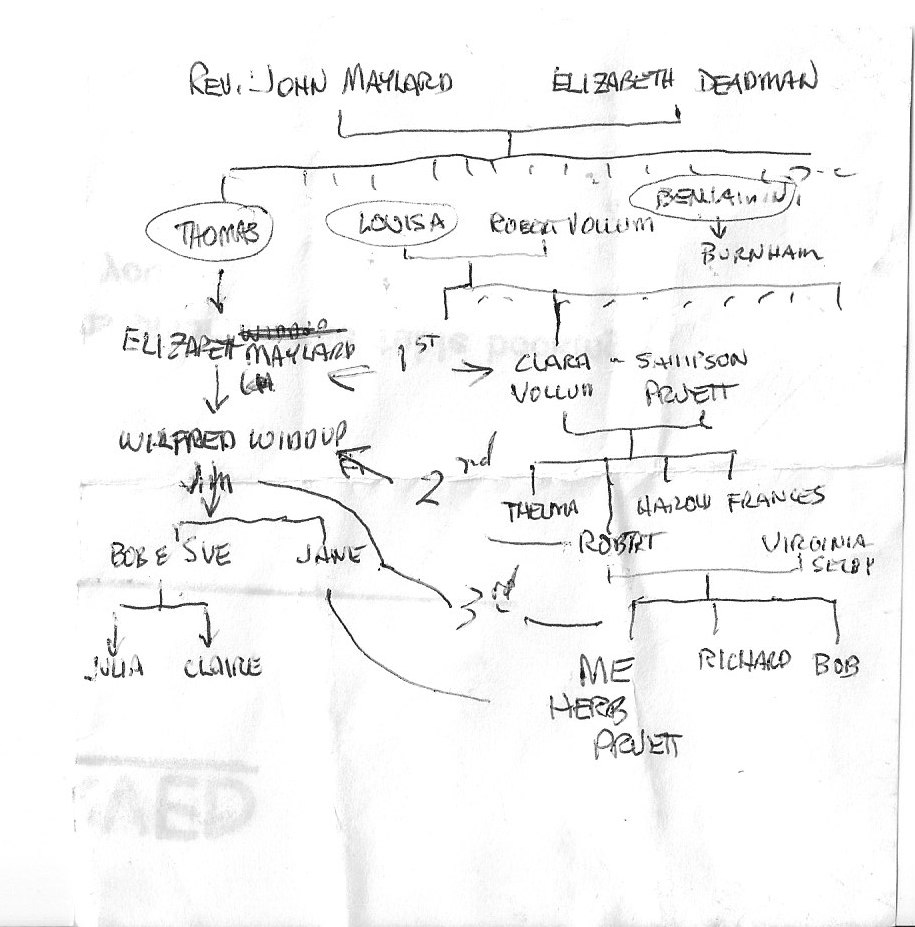

On the back of a menu card Herb – our American cousin – drew up our relationship in the form of a family tree.

People once living, breathing, walking and talking, confined to the syllables of their names, attached to each other by a horizontal blue ink line, each hanging off it in their designated time and space, like a family hangman game.

I remember thinking one day I’ll be one of those, waiting for someone like my sister to come along and press-stud me to my own horizontal line, my dates below me in brackets, framing the start and end of a lifetime of experiences. Attached to cousins four or five times removed I’ve never met, or even known of their existence. I hope they laugh at my jokes.

So far Wilfred has escaped detection. It’s not so much Who Do You think You Are, as Where Do You Think He Went.

The closest physical proof to his very existence is my dad. Scuttling around in his wheelchair, the family bridge between a long-gone generation and mine.

Dad still doesn’t know what happened to his dad. But a whole backstory of family history has opened up. It’s fascinating stuff.

Dad was tired at the end of the night, as you would be after chicken dinner AND vanilla ice cream at the age of 93. But thanks to my sister, we’d all shared in reaching out and touching part of his family history and he was happy for that.

But whether sister/Jessica/Miss Marple/the geneaology network will finally come up trumps in the search for a dad for dad only time will tell.

Sadly though, in dad’s case, we don’t know how much of that he has.